Really excited to see my article about climbing and exploring the Genyen Massif of Western China in the current issue of Rock and Ice Magazine!

Wild Wild West

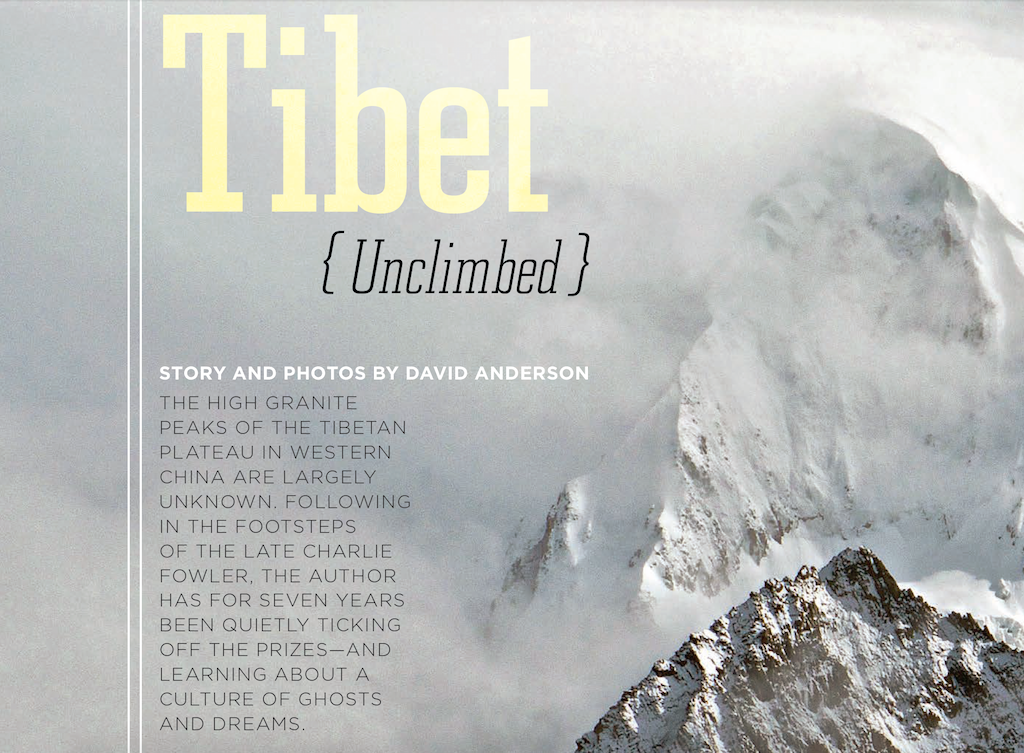

The Tibetan Plateau in Western China is home to a bevy of unclimbed 6,000-meters granite peaks. David Anderson has been to the region three times, quietly ticking off the prizes and learning about the culture of ghosts and dreams.

By David Anderson

Year of the Dragon: 2012

The friction pulling at my waist made it difficult to move forward. I looked back with frustration at the lead rope, sewn in tight stitches around the crumbling granite spires. I stopped climbing, flipped the rope over a fin of rock and yelled, “Belay On,” to Szu-ting. The wind snatched my words and carried them east through the building mist, down the exposed 7,500-foot flank of Kemailong and out into the hazy green fields of the Tibetan Plateau in Western Sichuan, China. Still bathed in sunlight, the grasslands calmly pumped thermals of warm air into the sky, fuel for the towering thunderheads bearing down on us.

While climbing the summit ridge, I was able to disregard the building electrical storm. But as I belayed, it was impossible to ignore all my metal climbing gear ringing like tuning forks. Sparks leapt between the gear, my hands and the wet rope. Fixed to the mountain, I was completely helpless, like a prisoner strapped to the electric chair wondering when the fatal switch would be flipped.

“Please hurry,” I begged Szu-ting who was frozen on a polished slab calculating the trajectory of her potential swing.

“I’m trying,” she snapped, her voice full of both fear and annoyance.

After Szu-ting arrived at the belay, I crawled across the ridge toward the steep east face and peered down through the approaching darkness at the unknown 2,300-foot wall. Did we have enough gear to get down the face?

Prone on the ledge, I winced as streaks of ground current arced between my helmet and my wet forehead. I placed a single #5 stopper in a small crack and rigged the ropes for a rappel. As I descended, my rappel device squeezed the soaked ropes sending a constant stream of icy water down my crotch. Hail obscured my view and thunderclaps deafened my ears. The uncertain decent below was our only hope.

The year of the Dog 2006

The impetus for my first visit to the Genyen Massif was a photo of the majestic 700-year-old Lenggu Monastery resting in the center of a narrow valley in Sichuan ,China, taken by famed Japanese explorer Tamotsu Nakamura and published in the 2003 American Alpine Journal. The most compelling part of the photo was the caption, which read: “The highest peak in the region is Mount Genyen (20,354ft) a divine (sacred) mountain which had been climbed in 1988. However, more than ten untouched rock and snow peaks of over 19,000 feet await climbers.”

The first person I contacted for logistical information about the area was friend and climbing legend Charlie Fowler. He wrote:

Hi Dave,

A lot of climbers contact me for information about climbing in Western China. I’m going to the Kang Karpo (Meili Xueshan) range this fall myself. There is no rule of law in these areas and things depend on your ability to negotiate and work with the locals. I’ve just done it on my own, paying locally as I go. Buying into a corrupt system doesn’t help the local people or climbers who will follow in your steps, remember that.

Charlie

On October 7, 2006, Americans Molly Tyson, Andy Tyson, Canadian Sarah Heuniken, and myself rendezvoused in Chengdu, the capital city of Sichuan Province. Chengdu is located at the bottom of large fertile basin on the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau. As a result of its topography Chengdu’s skies are constantly filled with clouds and haze. It is known as the city where dogs bark at the rare sun. This canine behavior gave rise to the Chinese proverb “shu quan fei ri” that means being surprised at something commonly seen, due to one’s ignorance. With the four of us having little understanding of the language, history or culture of the region, shu quan fei ri became a fitting motto for our expedition.

We left Chengdu in an overloaded Jeep Cherokee and drove west through the dense bamboo forests of the Qionglai Mountains, where a few wild pandas still live. Eventually, we emerged onto the high plains of the Tibetan Plateau, passing herds of yaks, tended by Tibetans who lived in hand woven black yak tents dotting the empty landscape.

In the village of Zhangma, 600 miles West of Chengdu, we hired horses and followed a small single track toward the Genyen Massif. We passed thick-walled Tibetan houses and fields of crisp barley swaying gently beneath the low ashen sky. Further up valley, we crossed wooden bridges cantilevered dangerously over roaring torrents of jade-colored melt water fed by unseen glaciers above. The long hike left the four of us spread out in the thin air, following our own solitary rhythm of breaths and steps as we climbed into the mountains.

At the day’s end, I stood before the Lengu Monastery and I smiled as my eyes drifted outside the frame of Nakamura’s photo to a stunning granite spire. But before we could celebrate our discovery, two monks with dour faces approached us.

We learned an expedition from Italy had climbed the sacred Mount Genyen in the spring. As a result, the monks were not happy more climbers had arrived to possibly do the same. When it comes to sacred peaks climbers often walk a thin line between respect and personal desire. Some climbers have tried to reach a compromise, at least in their eyes, by stopping a few feet short of the summit. This tradition was adopted by Joe Brown during the first ascent of Kangchenjunga in 1955 and was also used by Karl Unterkircher when his Italian team climbed Genyen earlier in the spring.

Eventually, we were able to convince the monks we had no desire to climb Genyen, but we were very interested in the rock pinnacle jutting out of the hillside behind the monks. “Sachun,” the older monk said.

On the glacier below Sachun (18,753 feet), Sarah and I roped up and passed several gaping crevasses. The sun hit us as I booted up steep snow on the east side of the peak. Transitioning to the rock headwall, Sarah calmly slotted the picks of her axes in thin seams while balancing her front points on tiny edges. More pitches of perfect granite cracks led to a small col below the summit. Above me a 25-foot unprotectable slab guarded the summit. I moved slowly, treating the delicate 5.10 climbing with the respect it deserved. The wind picked up as I neared the top and I shamelessly walrus-ed onto the summit. I looked around for cracks, horns or other features to place protection, but it was as if I had climbed onto the smooth back of a giant whale. With Sarah out of earshot and no options for building an anchor, I immediately started to down climb. My damp shirt shot cold waves of fear up my spine. My movements tightened and my legs began to shake. “Stop it,” I hissed at my legs as if they were a couple of unruly teenagers. Part way down the slab, I weighted a large crystal foothold and it snapped. The fall started slowly at first and I had time to look down at my potential impact zone. I didn’t have many options. If I folded my hand, the consequences would be a 20-foot femur-snapping fall into the rocky col directly below me. So instead, I bet everything on the unknown and pushed myself off into the void of the west face. As I fell, my body pirouetted out of control, arms and legs fighting with the Himalayan air. I flew past the col and continued gaining speed. After falling almost 30 feet I impacted on a flat ledge fortuitously covered with several feet of soft snow. Hastily clearing the snow from my face, I leapt out of my flight-induced crater to prove to myself that I was still in one piece and incredibly I was.

I had been back in the States a few weeks when I received a phone call from Mark Gunlogson, the president of the guide service Mountain Madness. “The reason I am calling,” Mark said, “is Charlie Fowler and Christine Boskoff, [who owned Mountain Madness,] missed their return flights from China and nobody has heard from them in a couple of weeks. The last e-mail indicated they might be heading to the Genyen region.”

“Genyen?” I choked out. I listened to Mark give the few details of what they knew about Charlie and Chris’ time in China, but my thoughts were elsewhere. After I hung up the phone, I re-read the e-mail I sent Charlie right after I returned from China.

“Hey Charlie,

Just wanted to thank you for all your advice about traveling and climbing in China. We ended up going to the Genyen Massif in Western Sichuan. We had stellar weather and did some great climbing. The area has lots of potential and is truly a magical place, you should check it out sometime.”

I first met Charlie in Patagonia. I remember watching him slack line, barefoot in Campo Bridwell, taking note of his amputated toes from an epic decent from Gurla Mandhata in Tibet. During the next few years I would occasionally bump into Charlie and Chris cragging in the U.S. Charlie always had a friendly grin and confident swagger that came from a lifetime spent riding the edge of his abilities and mountain sense.

It was a few days after Christmas, when the search team found Charlie’s body at 17,000 feet on the north side of Mount Genyen. He was wearing his pack, missing a glove and his camera. Maybe he was taking a photo of Chris or Genyen itself when something hit them? Rock or serac fall—no one will ever know. The discovery of Charlie’s body had at least produced some type of closure (Chris’s body would be located the following spring). For me, the tragic news changed the Genyen Massif from a stunning mystical range full of wild climbing objectives to a cold place in a far away country, where one of my heroes had died.

The Year of the Dragon: 2012

In the village of Lamaya, Juzha spooned out two heaping dollops of fresh yak yogurt into my bowl. From a nearby glass jar he grasped a handful of coarse sugar grains and tossed them onto the surface of the yogurt as if he was casting a spell.

We had just finished negotiating a fair price to have our gear and supplies transported by horses to the base of Kemailong, 20 miles and four valleys to the northeast of Mount Genyen.

I first caught a glimpse of Kemailong in 2006; its striking double summits, of steel gray granite, looked like dueling swords thrust up out of the rolling green fields. Nakamura listed the peak as 18,963 feet and that was all the beta we had.

I was traveling with my fiancée Szu-ting Yi. Szu-ting had grown up in Taiwan and hadn’t discovered outdoor pursuits until she moved to the U.S. for her PhD. She quickly took the determination she had honed in academia and applied it to her new passion in climbing. It was her interest in my 2006 expedition that had helped me separate Charlie’s death from the beautiful peaks of the Genyen Massif and rekindled my desire to return.

From the courtyard, where the horses were being readied for the trek, we heard several men arguing. Szu-ting and I walked out of the house and found our climbing gear duffels unzipped with the men shaking our ice axes in the air with a look of fear in their faces. We discovered their anxiety was directly related to the deaths of Charlie Fowler and Christine Boskoff. In 2006 when the search for the two famous American climbers had narrowed to the Genyen region, suspicion for their disappearance fell upon the local villagers and the monks of the Lenggu Monastery. Using the guise of searching for clues about the missing climbers, the police had ransacked the monastery, interrogated the monks and rifled through their personal belongings. The police also rounded up the Tibetan horse packers here in Lamaya, including Juzha, and threw them in jail on the suspicion they had something to do with the climbers’ disappearance. Later, when the bodies of the Fowler and Boskoff were discovered, Juzha and his fellow horse packers were released, but the scars remained.

The fate of our expedition seemed to hang in the balance, weighed down by the actions of those who came before us. With a confident smile, Szu-ting began to work her negotiating magic. Being from Taiwan, a country China claims as its own, she shared with the Tibetans the mistrust of the Chinese government and the knowledge of the Communist’s history of human rights abuses.

After much conversation, Szu-ting began writing Chinese characters on a pad of paper. She crafted a waiver stating the horse packers and people of Lamaya would not be responsible for anything that happened to us in the mountains

“Write your passport number and sign it,” Szu-ting commanded, handing me the pad. I followed her instructions while Juzha held out an inkpad, so that I could add my thumbprint to seal the document. The over-the-top release satisfied the horse packers’ worries, climbing gear was strapped to the horses and we began the trek to Kemailong

By evening we were camped on the western edge of a large meadow below a series of empty meditation caves. Through the yellow blaze of the cook fire Juzha asked why we wanted to climb these peaks. Was there money to be made or a better social status to be gained? Szu-ting and I looked at each other and laughed. Juzha shook his head in disapproval telling us that we should be having kids, making a future instead of risking it climbing these mountains. Juzha then jokingly warned us about the wild creatures of Kemailong. He told us about bears, leopards and even wild men who lived in the woods beyond the meadow, killing stray yaks and anything else that wandered into the tangled rhododendron forest. As the fire burned down, Juzha’s voice took on a serious tone. “There are spirits here, too,” he said while looking directly into our eyes. He pointed toward Kemailong. “There are spirits up there, some good, some bad, they are watching us, maybe one day my spirit will be there as well,” he added with a trace of a smile.

On October 1, after a week of unsettled weather, I unzipped the tent at our high camp and stepped out into the still night air. My pupils widened and the stars and planets began to appear, like tiny cookie cutters in the dark dough sky above and I knew tomorrow would be our chance.

Racking up in the pre-morning light, our chosen route up the south ridge looked to be around 1,500 feet to the summit. After a few mixed pitches we reached the ridge and traded leads on the featured, yet compact granite. Pitches of dry sunny rock fell easily below our hands and feet. Down in the valley, I could see a few clouds building, but otherwise the weather seemed stable. We were making good progress up the moderate terrain, but it was also apparent that I had grossly underestimated the length of the ridge.

“When I run out of rope, just start climbing,” I said to Szu-ting as we exchanged gear at the belay. Partners on the rock and in life, we moved together along the arching ridge for more than 1,000 feet, believing in each other’s climbing ability to keep us safe. To the south I could see the fluted ridges of Mount Genyen’s north face standing tall like the columns of a Roman temple and I indulged in the past, imagining Charlie route finding up the steep face with Chris close at his heels.

After I ran out of gear, Szu-ting led the final pitch to what we thought would be the summit, but instead of raising her arms up in celebration, she stared off to the northwest. When I reached her, I looked across a convoluted ridge of crumbling granite gendarmes adorned with clumps of hardened snow. At the end of the ridge, 600 feet away, stood a granite tower.

“I don’t even know if that thing is any higher,” I said while re-racking the gear. “We should call this the summit.” I was still complaining about the absurdity of needing to go to the true summit as I led out towards it. After an hour of navigating the tricky traversing terrain, we stood below an overhanging crack guarding the top. I jammed my fists into the fissure and fought upwards. By now the haze in the valley had risen up to the neck of Kemailong and a wall of black clouds were advancing from the west. The first blinding flash of lightning and the crash of thunder came simultaneously. Terrified, we reversed the ridge and began the descent of the east face.

Initially, cracks to build anchors appeared near the end of each rappel, but several rope lengths down I had to settle for a flaring slot running with water. I placed a tipped out three-inch Camalot and bounce-tested it until my harness cut into my hipbones. Szu-ting arrived and eyed the single piece warily before committing her full weight at the hanging stance. The cold and accumulated stress was wearing us out and as we continued down the descent began to feel like runaway train that we were barely keeping on the track. I lost count of how many rappels we had done, but the darkness kept me guessing about how many more we had to go.

“I am at the end of the green rope,” Szu-ting yelled dangling 50 feet above my stance. I stopped fiddling with the anchor and flashed my headlamp across the face searching for the green rope that had been right next to me.

“I made a mistake” Szu-ting called down in an apologetic tone.

“What do you mean? What kind of mistake?” I shouted back, struggling to control the rising panic in my voice. But the gusting wind prevented further communication and all I could do was stare upward at Szu-ting, hanging limply on the end of the rope out of my reach.

I had held my shit together through the run-out climbing and lightning strikes on the summit, but standing alone on a six-inch ledge powerless to help the woman I loved, I began to crumble. The enormity of the sheer rock face seemed to grow above and below me. My head spun with vertigo and my stomach churned. When I closed my eyes, all I could see were dark images of selfish climbing desire: The police imprisoning the monks and Juzha, the bodies of Charlie and Chris in the avalanche debris, my fingerprint on the signed “release” note and Szu-ting falling into the darkness.

I snapped my head back and sucked large gulps of air, trying to shake visions of the unthinkable. I looked away from the lifeless wall of rock and snow and out towards Lamaya. Below me, through the swirling clouds, I thought I saw a distant light. I blinked trying to shake the fear-induced mirage, but the reticent glow remained. It appeared to be a light from a large fire in the meadow near where we first camped. I concentrated on the light watching it flicker through the storm. Was it Juzha coming to look for us or other nomads grazing their yaks? Or the wild spirits he had described? I didn’t know if they could see our headlamps bouncing off the frozen granite 7,000 feet above them, but in my moment of despair it felt comforting to see their light.

“I’m sorry, I made a mistake,” Szu-ting yelled again through a break in the wind. Climbing for 16 hours, out of food and nearly hypothermic, Szu-ting had made a big mistake. She only threaded the purple rope through her rappel device. What saved her was an auto block back-up she hitched around both the purple and green ropes. As she rappelled, the green rope had slipped slowly through the rappel anchor leaving her 50 feet short of my stance.

Szu-ting pendulum-ed back and forth across the blank face until she found a crack to accept a piece gear, evened out the ropes and few minutes later reached my ledge. After about 13 rappels, we finally stood on the remnants of the dying glacier at the base of the east face of Kemailong. We pulled our ropes and stumbled like drunks through the snow-covered talus searching for the tent and the end of our epic.

The following day, when we reached the pasture where our base camp had been, I heard the unique sound of advancing hooves drumming on thin soil. To the East, four horses broke over a low rise and galloped towards us. Their powerful chest and thigh muscles drove their hooves into the ground flinging chunks of sod in their wake. Twenty-five feet away the horses halted, ears up with no hint of exertion and stared at us. Pinned against the edge of the pasture Szu-ting and I stared back. They were not Juzha’s horses. After a few moments we walked past the horses, hoping to find their owner to transport our monstrous packs back to Lamaya. I realized the horses’ keeper must have been the person who built the fire I had seen during our rappelling nightmare. My shoes pushed through the wet grass until we reached the edge of the meadow but we encountered no one and saw no sign of a recent fire. I cinched the waist belt of my pack tighter and looked back up valley at the peaks covered by clouds. My eyes followed Kemailong’s lower ridge down past pockets of mist clinging to the granite boulders and finally to the western terminus of the meadow where the horses should have been, but strangely they were gone.

Descending through the twisting valley, I had hours to reflect on my time here. As much as I wanted to believe that my skill and hard work had alone shaped my experiences in the mountains of Western China, I could not put aside a number of events that defied logic, whose outcomes seemed bounded by luck, fate or something else. I thought about the unlikely snow covered ledge that cushioned my fall on Sachun, Charlie and Chris’ fatal visit to Genyen just after mine, the lightning storm on the summit of Kemailong that spared our lives, and the fire and horses I had seen in the meadow. These events couldn’t be fully explained. Eventually, I stopped looking for answers and let the strange incidents rest.

In a time before Buddhism spread north from India, before the Chinese government divided up the land and before foreign climbers, like myself, came to test themselves in a place they didn’t really understand, the people living in these valleys looked to the spirits to guide them and give them hope. Some good, some bad like Juzha said. I smiled and continued hiking, with my eyes wide open, into the blustery wind.

David Anderson has made three trips to the Tibetan Plateau in Western Sichuan, China, coming away with first ascents on Sachun (18,753 feet), a “Patagonia-like” spire, via Dang Ba ’Dren Pa (5.10+ A0 M5 70°) in 2006, the West Ridge (IV, 5.7, 60°) of the previously unclimbed Crown Mountain (18,373 feet) in 2011, and the south face of the striking granite tower Kemailong (19,259 feet) via Joining Hands (V, 5.10, M5) in 2012.